Despite Bosnian economists’ claims that China is motivated solely by economics, it seems the “irresistible charm of authoritarian growth” may seduce many countries to succumb to Chinese political pressure, and even embrace grave violations of human rights.

Written by: Edina Bećirević

“The irresistible charm of authoritarian growth”[1] is a sentence that aptly sums up China’s current position in the Western Balkans. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic China was openly favoured by Serbia over countries in the West as a source of aid and information, a stance also taken by some politicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Yet even prior to the pandemic a network of political and academic actors in the Western Balkans were engaged in a campaign to celebrate China as the world’s new leading global power, overlooking the fact that China is a communist, authoritarian regime that is committing genocide against Uyghurs. The aim of this campaign was not only to favor China as the country to look up to, but also to undermine significant economic investments by the EU and the US, as well as their initiatives to strengthen the rule of law and promote democracy in the Western Balkan countries. Intentionally or not even liberal-oriented regional media have followed this lead, promoting China but also Russia and some other authoritarian regimes as alternatives to the Euro-Atlantic model.

IS CHINA ONLY INTERESTED IN ECONOMICS?

When assessing the influence of China in the Western Balkans even experts and politicians with a more liberal orientation have taken little issue with the negative effects of Chinese investments in the region, and most have ignored the intensified activity of the MSS (China’s foreign intelligence service). Few have raised concerns about cultural and educational exchange programs that have the potential to promote illiberal values in Western Balkan societies, where the fractures of war may make them particularly susceptible to this messaging. The dominant narrative is that China, unlike Russia, not only “doesn’t have an alternative political vision” for the Western Balkans, but that it supports a European outlook for the region. As such, the political interests of China are viewed as limited mostly to whether sufficient stability exists to support its economic investments. As one Bosnian economist told me, “capital goes where it can grow, and that is the primary motivation of the Chinese government.”

But nothing has more clearly proven the naivety of the idea that China’s economic projects can exist in isolation from its politics than Serbia’s willingness to officially support Chinese genocide against Uyghurs at the UN last summer. Given that Serbia’s accession negotiations with the EU are underway, and according to some estimates should be completed by the end of 2024, Belgrade could be expected to follow the EU on foreign policy. Instead, after 22 states – largely from the EU – issued a letter to the United Nations Human Right Council condemning China’s treatment of the Uyghurs, Serbia chose to sign on to an opposing letter which credited China for “protecting and promoting human rights through development.” In doing so Serbia joined 49 authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes including Russia, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia and, notably, 23 Muslim-majority states. Some of these signatories supported China because of their own economic interests, and others because of their own vulnerabilities on the issue of human rights.[2]

THE BOSNIAN EXPERIENCE

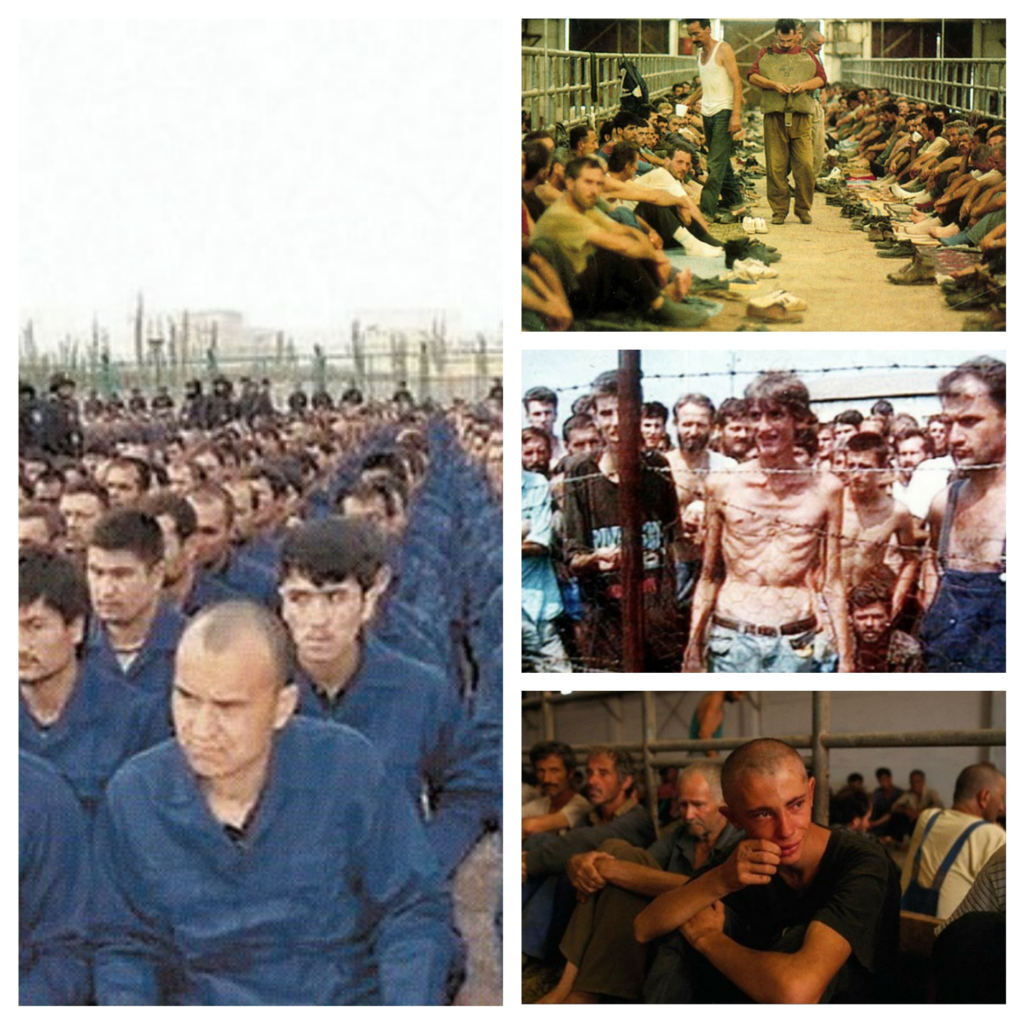

It should not be surprising to European diplomats that Serbia has readily supported China on this issue. Taken Serbia’s past involvement in the Bosnian genocide and its present narratives of genocide denial, this was actually one of the more sincere reflections of Serbian policy at the UN. Yet Serbia is not the only country in the region supportive of China in this matter. In other Western Balkan countries mainstream media, academics and politicians have also been curiously silent about the genocide of the Uyghurs. Perhaps saddest is the silence of Bosniaks, who were so recently the victims of genocide. They were held in very similar camps to the Uyghurs, run by the Bosnian-Serb leadership under the auspices of the Serbian state. In Bosnia and Herzegovina some have called them “detention camps”; in China they are called “re-education camps”. Make no mistake, as was the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina so in China now these terms serve as euphemisms for concentration camps.

In 1992 images from camps in Omarska, Trnopolje, and Manjača in northwest Bosnia and Herzegovina provoked global consternation about the war. Brave journalists such as Roy Gutman, Ed Vulliamy, Peter Maass, and a British TV crew from Independent Television News (ITN) were so persistent in demanding access to these sites that they managed to enter and interview some of the “human skeletons” they had photographed behind the barbed wire. But in China, the suffering of Uyghurs cannot be filmed and photographed. Chinese authorities have closed the Xinjiang region, leaving the world to rely on satellite images, locations secretly filmed by drone cameras, and the testimonies of witnesses who have either served a sentence in “detention” handed down in a sham trial, or have managed to escape. The torture described by former prisoners includes rape, beatings, forced sterilization, and various psychological abuse. Some prisoners have also been sentenced to death, but there is no reliable data on how many Uyghurs have been killed by China.

China’s growing economic power in the world means that we may never learn the scope of the Uyghur genocide. Unlike Serbian and Bosnian-Serb leadership, China has the capacity to ensure that its mass graves are never unearthed. Still, even before mass graves were discovered in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the genocide against Bosnian Muslims provoked the outrage of the West as well as of majority Muslim countries, even uniting enemies such as Saudi Arabia and Iran to lobby for their “Muslim brethren” in international spaces. Uyghur Muslims have not been afforded this support, exposing the hypocrisy of many Muslim countries.

THE GEOPOLITICS OF EMOTION

There was much talk last year about how Turkish President Erdogan has returned dignity to the Muslim world by ordering the reclassification of Istanbul’s historic Hagia Sophia as a mosque after the annulment by the Council of State of a 1934 presidential decree establishing it as a museum. The Turkish president is well versed in projecting himself as a protector of Muslims around the world. The “geopolitics of emotion” is his trademark. And while Turkey did not sign the letter to the United Nation Human Rights Council in support of China, and has condemned the treatment of Uyghurs in the past, when Erdogan met last summer with President Xi he reportedly emphasized that “residents of various ethnicities [are] living happily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region thanks to China’s prosperity,” calling this “a hard fact” and noting that “Turkey will not allow anyone to drive a wedge in its relations with China.”[3] In light of this statement, the extradition treaty between China and Turkey which the Turkish Parliament is getting ready to ratify will further endanger the position of Uyghurs.

This appears to be the default position of autocrats these days, and one that poses a challenge to the United Nations – especially considering that these like-minded authoritarian states gathered in more than double the numbers of those willing to condemn China at the Human Rights Council. As autocratic and authoritarian regimes work to dismantle international human rights standards and norms from within the United Nations, experts in the Western Balkans and elsewhere must recognize that Chinese economic investment is indeed intertwined with politics. For despite the assertion of Bosnian economists that China is motivated solely by economics, it seems the “irresistible charm of authoritarian growth” may seduce many countries to succumb to Chinese political pressure, and even embrace grave violations of human rights.

[1] Sentence borrowed from the book Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu & Robinson (2013).

[2] https://jamestown.org/program/the-22-vs-50-diplomatic-split-between-the-west-and-china-over-xinjiang-and-human-rights/

[3] (Al-Araby, July 3) https://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/world/2019/07/03/Erdogan-says-people-live-happily-in-Xinjiang-Chinese-state-media-